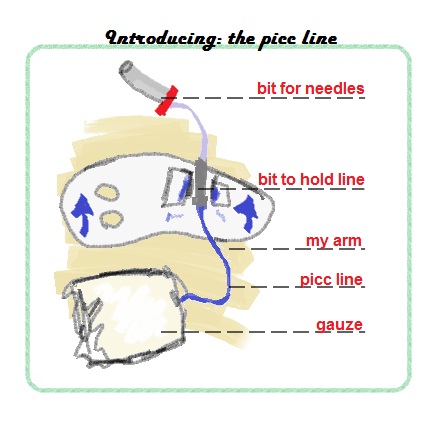

Finally I can write about the picc line. Here it is folks: having a picc line installed in your arm.

As you know, the consultant booked me in for the very next day – this whole thing was a whirlwind. Apparently she called the nurse who inserts the line and begged to add me to their list: ‘very persuasive’ said my picc nurse. Thank goodness for strong women with curly hair.

As you know, the consultant booked me in for the very next day – this whole thing was a whirlwind. Apparently she called the nurse who inserts the line and begged to add me to their list: ‘very persuasive’ said my picc nurse. Thank goodness for strong women with curly hair.

Zsolt and I arrived at radiology around 1.25, my appointment was for half past. Before we could sit down a short haired nurse appeared from the hallway and asked: are you Catherine Brunelle?

That’s my name, don’t wear it out. (I didn’t actually say that)

‘Here you go, put this on.’

She gave me a robe – which I put on backwards at first – and I changed. It was a typical hospital gown with faded colours, thin strings, no coverage . . . anyhow, typical. Thank goodness I kept my jeans.

Next we (Nurse Picc, Zsolt and I) headed down a maze of white bright hallways till we reached a room filled with busy nurses. “We’ve got another list so we’re rushing now,” says the nurse. I nod despite not understanding.

Anyhow, the room where the picc line is inserted has a very large machine as its centrepiece. This machine has a table, all kinds of cords and a giant circular x-ray camera thing, plus monitors on the side.

(All the while Zsolt has been with me. The nurse did say “and you’ll have to go when we start” but then I said, “Can’t he just stay for the needle?” and she caved. He was suited up with x-ray protection and allowed to hold my sweaty hand during the entire procedure.)

First: she scans my arm with an ultrasound and checks if my veins are accessible. The ultrasound machine has this clear rubber piece that glides over your lubricated skin. The gel is cool, but the ultrasound is totally painless. Ultrasounds are the best; my number one pick for interior body scanning.

Second: Assuming a good vein is found, a tourniquet(?) is placed on the upper arm, and you are asked to lay on the table. Picc lines are generally inserted around the inner elbow or slightly higher, because the veins widen there.

Third: The nurse will sterilize the area – it smells like hydrogen peroxide. Have you ever used those bristle scrubbers to wash dishes? Well, think of that on your arm. Not painful, but very hygienic and smelly.

Fourth: Numbing the pain. (Zsolt came around the table to hold my hand as this all began.) The nurse has you lay out your arm on a side plank attached to the table. I looked away during this, but essentially a needle is given to numb the pain. This stings, but is most certainly worth it. Numb = good.

Fifth: It begins. Using the ultrasound the Nurse Picc is able to insert a catheter into the choosen vein. Then it’s all down to stringing in the line. I didn’t feel too much, but apparently some people feel a bit of pressure as the tube moves along.

Sixth: Tube in place, an x-ray is taken of the chest area. When I say x-ray, I mean a video. Zsolt could see my heart pumping on the monitor (he has seen way too much of me now. . . my bones, my heart, my guts . . . not so romantic.) and the nurses used this to judge whether the line is in place.

Seven: Wrapping up. Literally. My arm was insulated from the outside with layers of bandages and gaze, which needs to be changed every week. This past friday I had the dressings refreshed, and the nurse laughed at how much they’d put on. Now I have less – much less – and can actually see my arm.

So that is it. Following insertion I went right to chemo, which is an entirely different story I’m not ready to write about, however, the picc line worked very well. No sore veins!

And that is the story of picc.